22 September 1914: Remembering HM Coastguard’s greatest loss

As the nation remembers members of the armed forces lost during military service, HM Coastguard laments the tragic loss of more than 1,000 sailors on 22 September 1914.

When we think of the Great War, we think of tremendous battles fought in far-flung foreign lands; Passchendaele, The Somme and Gallipoli being frequently brought to bear in the public consciousness more than a century later.

However, a devastating naval attack closer to home was to lay bare the significant threat posed by Germany's state-of-the-art underwater war machines. Over the course of a dark and fateful day in September 1914, more than 1,400 were to lose their lives aboard three vessels defending the North Sea.

Among those lost were a substantial number of coastguards, drawn into military service at the start of war with Germany. The tragedy was to be the greatest loss of personnel in the coastguard service’s history.

A threat to Naval supremacy

At the turn of the 20th century, Britain’s naval fleet - one of the most impressive and powerful in the world – had begun to feel the pressure.

Growing German naval power, fuelled by Kaiser Wilhelm II’s desire to rival the British fleet, had provoked demand for bigger, better and more powerful ships among the Admiralty.

This challenge to British supremacy was no more acutely felt than in British corridors of power, where dangers to the island nation’s vital imports posed a considerable risk to economic survival.

Between 1900 and 1914, huge advances were made in naval shipbuilding and engineering, rendering ships built at the earlier end of the period outdated and outclassed by faster and better-armed German Destroyers.

Cruiser Force C – 'the Live Bait Squadron'

To counter the threat of German incursions to the English Channel, the 7th Cruiser Squadron, ‘Cruiser Force C’, was established, comprising five Cressy class armoured cruisers recalled from reserve service to patrol shallower waters off the Dutch coast – the ‘Broad Fourteens’.

But who would board and man the ageing patrol, perhaps forebodingly referred to as ‘the Live Bait Squadron’?

A cadre of naval cadet officers, some as young as 15, were taken from the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth, and with its members drawn from retired and discharged Royal Navy personnel, HM Coastguard seemed to offer invaluable maritime skills and sea-faring experience as crew, having upkept their military service with ‘drill service’ aboard Naval ships.

The fate of HMS Aboukir, Cressy and Hogue

Unbeknown to them at the time, an even greater threat to patrolling 12,000ft armoured cruisers HMS Aboukir, Cressy and Hogue lurked silent, deep beneath the waves – German ‘U-Boat’ U-9.

Although initially dismissed by both the German and Royal Navies, who’d experienced more submarine losses than successes at the outset of war, submarines were soon become a lethal new naval predator.

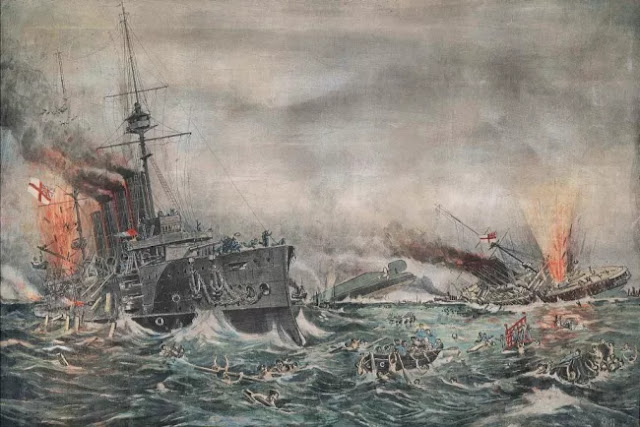

And when U-9’s first torpedo found its mark on the morning of 22 September 1914 to make an immobilising strike on Aboukir’s Engine Room, it set in motion a calamitous turn of events made worse by a costly underestimation of submarine warfare.

Initially believing the vessel had collided with a mine, both HMS Cressy and Hogue rushed to the capsizing flagship’s aid. It was a fateful decision. Capitalising on the confusion, German U-Boat Captain Otto Weddigen then directed his 29 crew to unleash torpedoes at HMS Hogue, which met the same fate just ten minutes later.

Spotting the surfacing U-Boat, HMS Cressy opened fire alone and attempted to ram the submarine, which was able to release a salvo of torpedoes at even closer range. After a huge explosion in the ship’s boilers, Cressy was capsized and lost beneath the water in less than half an hour.

Men toiled in the freezing waters as would-be rescuers from two Dutch sailing trawlers in the vicinity were paralysed to respond: a fear of mines blighting their willingness to respond.

Dutch steamers Flora and Titan and Lowestoft sailing trawlers Coriander and J.G.C were first on scene, before the arrival of British Destroyers some two hours later.

The brutal cost of war

Despite the rescue of 837 seamen from the three vessels, 1,459 men perished in the attack with 560 sailors lost aboard HMS Cressy, 527 aboard Aboukir and 377 aboard Hogue.

With a majority of crew being retired Royal Navy personnel, the incident represents the single greatest loss of coastguard personnel since the service’s modern incarnation in 1822. The catastrophic loss of life was to change naval warfare forever, demonstrating the immense power -and danger – posed by the submarine.

With such devastating losses so close to home weighing heavily on British morale at the time, the Admiralty was duly prompted to relocate a majority of coastguards back to mainland coastal duties.

Remembering the fallen, 110 years on

Director of HM Coastguard Claire Hughes has paid tribute to those lost to armed conflict as members of the armed forces. She said: “This month, we remember all of those who fought and died to afford us the freedoms that we enjoy each and every day. In times of war, HM Coastguard has been called upon by our nation to serve in the armed forces.

“Of particular poignance is the tragic loss of more than 1,000-crew serving aboard HMS Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy in 1914 which included many members of HM Coastguard. Their bravery, sacrifice and selfless devotion to the cause is something that all coastguards feel great affinity towards.”

She added: “We’re proud to see our coastguard colleagues representing the service at remembrance ceremonies across the UK, as the nation offers its gratitude to all those that serve in our armed forces.

“Through Remembrance, we come together to ensure that the sacrifices of those injured and killed in service are not forgotten.”